Table of Contents

The Sustainable Development Goals

What are the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?

Over a two-year consultation period, a set of universal goals addressing the urgent environmental, political and economic challenges we face were created.

Rounding off the unfinished business of the Millennium Development Goals, these new goals were designed to engage both developed and developing countries to achieve a better, more sustainable future for all.

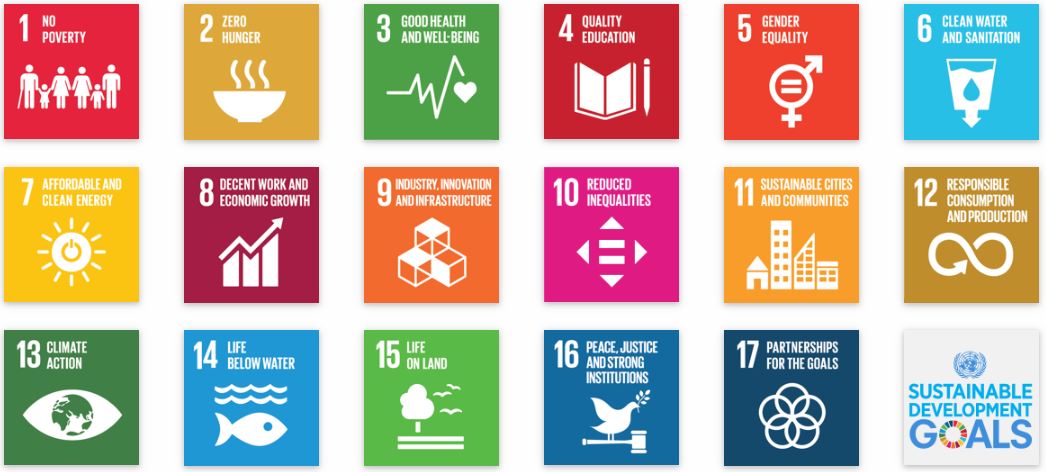

There are 17 goals, with 169 associated targets for human development, and a further 230 statistical indicators:

These are the UN Sustainable Development Goals (The SDGs). The UK, alongside 192 countries, signed up to the SDGs in 2015.

The formidable rallying cry was that will ‘no one [would be left] behind’, but how reasonable are these goals today? How relevant are they and how likely is it that organisations, groups and individuals can rally round and ensure the practical realisation of the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030?

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

How is the UK performing?

Despite the UK playing an instrumental role in the development of the SDGs, the UK has arguably lost its focus.

The pledge to ‘leave no-one behind’ hasn’t been realised in practice. The ‘measuring up’ report conducted by key stakeholders on the performance of the UK in relation to the SDGs shows how the UK is performing.

From this report, it is apparent that the UK performs well on 24% of the targets, has performance gaps on 57%, and shows little to no policy change or otherwise poor performance on 15%. Furthermore, for 3% of the targets, there was not enough data to make an informed assessment.

This sends a clear indicator that more needs to be done to ensure that the UK is committed to the policy of ‘leaving no one behind’.

Furthermore, Bond’s recent performance report on The UK’s global contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals highlights specific policy incoherencies.

The UK government, for example, continues to subsidise the use of fossil fuels while simultaneously recognising the need for developing countries to move to greener models of energy production.

What is more, this inevitably causes more significant confusion and inconsistency across policies.

The goals are interconnected and exist as a comprehensive framework. Unless considered together, progress on one goal is more likely to undermine progress against another

.

Are we running out of time?

The general narrative on the Sustainable Development Goals is that we don’t have any time to waste.

While innovations in healthcare are allowing people to live longer and healthier lives, 844 million people lack access to safe water.

While there is some progress towards the realisation of the goals, questions remain concerning the formidable nature of the goals.

Are the goals too ambitious or are global leaders and communities not ambitious enough in their pursuit and discipline towards achieving the goals? What is plain is that a worldwide effort is needed to achieve the SDGs.

Goal 2: Zero World Hunger

In 2017, the number of those in hunger across the globe increased from 804 million to just under 821 million, reaching a level not seen for almost a decade.

The failure to take effective action towards addressing goal 2 of the Sustainable Development Goals is closely connected to the increase in conflict and violence, and the increase in climate-related disasters across the globe.

Efforts to fight hunger must coincide with efforts to sustain peace.

Attention must focus on creating safe political environments.

Global hunger reflects the interrelated nature of the SDGs. A multi-prong approach is needed if effective outcomes are to blossom.

As for the UK, the UK government should develop and provide practical tools, guidance and resources for all UK government staff and implementing partners working internationally.

The UK’s role here will ensure proper cross-government mainstreaming of “leave no one behind” and will improve gender awareness and sensitivity and conflict analysis across all policies and programming.

Goal 13: The Environment

Secretary-General of the UN, Mr Gutteres, stated that there was a lack of political will concerning the environment.

To meet commitments, and “galvanise greater climate ambition”, he committed to convening a Climate Summit in September.

“Beautiful speeches”, he continued, are therefore not enough: leaders need to come equipped with concrete plans to reach these goals.

The UK should be leading the way for others to follow suit. Action should be taken on issues such as consumption, innovation and infrastructure to prevent the UK from falling behind other nations on poverty, equality and the environment.

Achieving sustainability and radical reductions in greenhouse gas emissions requires existing infrastructure to be renewed or replaced.

Public and private investment in new infrastructure needs to make significant efficiency gains and contribute towards a more circular UK economy.

What conclusions can we draw from this?

What is clear is that the Sustainable Development Goals cannot be viewed singularly.

Moreover, this threatens to endanger progress already made towards achieving the SDGs.

Thus, a holistic approach to policy is required if efforts to improve livelihoods and achieve a more sustainable future are to be realised. Actions and their consequences need to be viewed in the global context to ensure their effectiveness.

What are HAD doing to practically support the Sustainable Development Goals?

We train aid and development professionals internationally; we build on-the-ground effectiveness, strengthen governance, and drive innovation in leadership by capacity-building INGOs/NGOs across the globe.

Learning & Development:

Since our foundation in 2013 we have trained humanitarian staff from over 40 countries and counting.

Due to our access to some of the most hard-to-reach areas and our faith-based understanding we are able to train in humanitarian hot zones.

Some of our training attendees hail from countries such as: South Sudan, Yemen, Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq.

Learn more about the courses we offer

Research & Development:

In order to ensure that humanitarian and development programs and projects are well-informed by the needs of the community we conduct research that seeks to better understand development challenges faced in-country.

By carrying out original research we seek to generate new thinking on development and important topics such as climate change, healthcare, education and gender equality.

Learn more about our research projects

Talent Development:

The international relief and development sector has become increasingly complex and sophisticated, and as NGOs continue to grow, attracting and retaining the right interns who believe in our mission, are committed to our values, and aim to fill increasingly demanding, technical and challenging vacancies.

We are committed to continually engage and assist in the development and establishment of talented young individuals within the sector.

Learn more about our internship programme and graduate scheme

Over the last 4 years HAD has demonstrated its effectiveness in the development of young people having provided life-changing internship to 145 interns.

Through our association with Islamic Relief Worldwide, the Talent Development programme at the Humanitarian Academy for Development provides aspiring humanitarians with a range of entry-level work-based learning opportunities.

Through this individuals are assigned to a combination of practical work assignments and comprehensive training activities.

Talent Development supports young humanitarians who want to work in the sector.

Written by Charlotte Davies

Marketing & Communications Intern