Table of Contents

The Underlying Myth for FGM

How often have we heard the story of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from heaven, and the “Fall of man to earth”? Numerous times.

How many versions are there to this story? Again countless versions, from the ancient Greek religion to the Abrahamic faiths, as well as the additional fantasies of historians and folklore.

There is a striking detail in this story which in some interpretations, portrays Adam as a morally composed human being, swayed by his partner –Eve, who in turn, was easily enticed by Satan.

This interpretation is negated in Quran that narrates the whole story of Adam and Eve using “plural” tenses, blaming them both for their actions.

In ancient to contemporary narratives, the portrayal of women as natural transgressors and as having a predisposition to manipulation and deceit has accumulated over time to create social and cultural response to oppress and control women, their behaviour and their sexuality.

What is fgm?

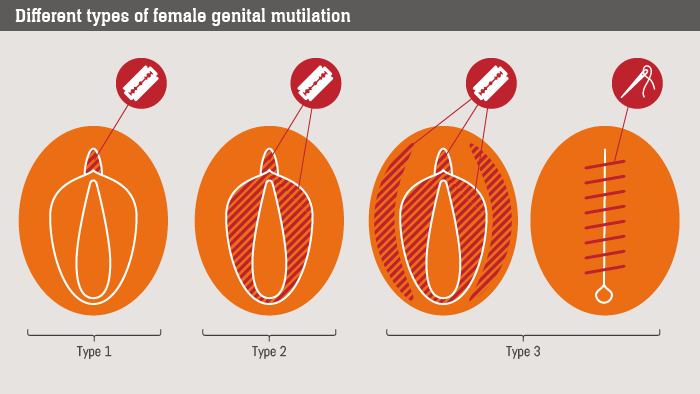

Type I:

Also known as clitoridectomy, this type consists of partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or its prepuce.

Type II:

Also known as excision, the clitoris and labia minora are partially or totally removed, with or without excision of the labia majora.

Type III:

The most severe form, it is also known as infibulation or pharaonic type.

The procedure consists of narrowing the vaginal orifice with creation of a covering seal by cutting and appositioning the labia minora and/or labia majora, with or without removal of the clitoris.

The appositioning of the wound edges consists of stitching or holding the cut areas together for a certain period of time (for example, girls’ legs are bound together), to create the covering seal.

A small opening is left for urine and menstrual blood to escape. An infibulation must be opened either through penetrative sexual intercourse or surgery.

Type IV:

This type consists of all other procedures to the genitalia of women for non-medical purposes, such as pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization.

Adam and Eve

Across the world, the practice of blaming “Eve” for Adam’s fall from heaven, continues to revive itself in many shapes and forms, one of which manifests itself as Female Genital Mutilation/ Circumcision (FGM/C).

It is the act of removing part or all of the external female genitalia.

There are 4 common types of FGM/C with almost 90% of cases being estimated to be of Type 1, 2 and 4 and about 10% are reported to be of type 3 which is the most severe form of FGM/C (see box 1).

There has been a lot of research to understand the origins of this act which is believed to be from ancient Egyptian age (Pharaonic).

Their motives are uncertain, however there is a clear line of evidence which links FGM to slavery. A 17th century report described a group in Mogadishu – Somalia “a custom to sew up their Females, specially their slaves being young to make them unable for conception, which makes these Slaves sell dearer, both for their chastity, and for better confidence which their Masters put in them. (Dos Santos in Freeman- Grenville 1962: 150)”

FGM/C was also practiced to prevent pregnancy in women and slaves and to protect women from being raped.

The most common reason for FGM

Controlling women’s sexuality is considered to be the most common reason for FGM/C.

It is encouraged to avoid “promiscuous” behaviour, as circumcised women are not easily aroused, and ‘virgin girls’ have greater marital prospects.

There is a tiny element of truth to this notion, as research has shown that circumcised women continue to suffer during intercourse, with reduced sexual desires and lack of pleasurable sensation.

Circumcised women and girls face many risks including painful menstrual cycles, recurring infections leading to infertility, problems during labour and child birth, depression and anxiety, difficulties urinating as well as bleeding and infection as a direct result of the procedure. Women with disabilities and/or other marginalised groups have an extra layer of overlapping vulnerability caused by FGM/C, however very little research has been done to explore their individual experiences.

Original motives

Original motives for FGM/C can still be reflected in our current time, varying from one context to another.

For some, it represents a cultural identity, for others it indicates a rite of passage into womanhood and some would still believe it’s a religiously-mandated practise.

Associating FGM/C to Islam is flawed, as the practice can be traced to pharaonic times which pre-dates the birth of Islam in the 7th century. It is also practiced in African and South Asian countries across different religions, ethnic, social and cultural backgrounds.

FGM/C has not been mentioned in the Quran and the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him did not advocate for it. It is also not practiced in many Muslim majority countries with both Sunni and Shia sects, such as Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Islamic Relief

As the largest Muslim faith based organisation, Islamic Relief have done extensive amount of work and research on FGM/C with a strong policy against this practice.

The harmful consequences of FGM/C contradicts with IRW’s faith inspired mission and as a result developed a case to actively advocate against it within its development and humanitarian programmes.

Islamic relief’s approach to eradicate FGM/C involves two key aspects: “including religion as part of the solution, and tailoring interventions to the specific needs and sensitivities of the community.” IRW worked with faith leaders in Ethiopia and Sudan to raise awareness amongst community members against this practice, which proved to be an influential approach to promote behavioural change.

Global statistics

Global statistics shows that majority of FGM/C reported cases (98% to 83%) are in Somalia, Guinea, Djibouti, Sera lion, Mali, Egypt, Sudan and Eritrea. However, with globalisation and high immigration rates, cultural practices also cross borders which makes it global phenomenon, with around 200 million girls and women undergoing the procedure every year and a further 3 million girls at risk of undergoing the procedure. FGM/C is considered violence against women and girls and a prevalent child protection issue that cannot be tackled by protection experts alone.A collaborative, multi-sectorial approach, with adequate resources that engages with all stakeholders, including faith leaders along with community based protection initiatives is required to tackle FGM/C.

As 6th of Feb marks the international day for zero tolerance to FGM/C, the world is advocating to reach this goal by 2030.Corresponding to our global commitment to “Leave no one behind”, it is important to acknowledge that girls and women with disabilities are 10 times at higher risk of violence.

Our hope for the future could be summarised by a prominent FGM/C activist who says “I have been cut but I will not cut my daughter”. Nevertheless, confronting such a socially-entrenched and complex issue is not without its challenges.As such, a much greater commitment from communities, faith leaders and international NGO’s is required to challenge this violent practise.

Written by Najah Almugahed

Gender, Inclusion and Protection Advisor, Islamic Relief Worldwide